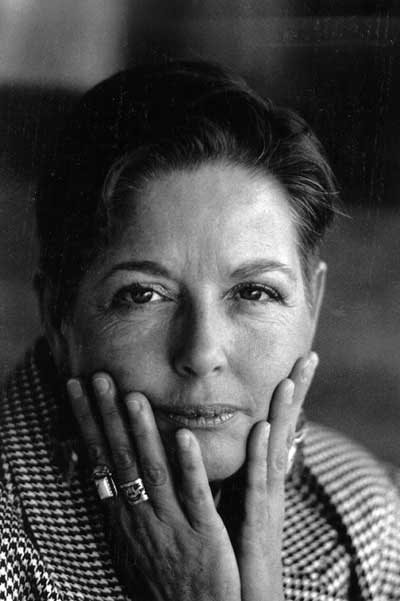

Beth

Brant

(Degonwadonti) -- Writer

Beth

Brant

(Degonwadonti) -- Writer

I figure by now most readers know me as

"that Mohawk lesbian," or "that nice Indian Granny who lives in

the States." Both statements are true. And I know who I am -

something I couldn't have said years ago when I was a battered

woman, a self-hating half-breed, a woman who self-destructed at

every turning, before I acknowledged my lesbianism and before I

began to write. Anyway, most of my stories are about lesbians

and gay men; all are about Indians.

—"To Be or Not To Be Has Never Been the Question"

Writing as Witness: Essay and Talk by Beth Brant

Beth Brant is a Bay of Quinte Mohawk from the

Tyendinaga Mohawk Reservation in Ontario, Canada. Her paternal

grandparents moved from the reservation to Detroit, Michigan,

where Brant was born in 1941. Her mother was white (Irish-Scots)

and her father was Mohawk. Because her mother's family

disapproved initially, at least, of her marriage to an Indian,

the Brants went to live with the father's family in Detroit. The

racism experienced from her mother's side of the family may have

been one of Brant's first experiences with it. Addressing racism

is one theme that appears often in Brant's writing. In the essay

"From the Inside Looking at You," from Writing as

Witness: Essay and Talk (1994), Brant asserts "when I use

the enemy's language to hold onto my strength as a Mohawk

lesbian writer, I use it as my own instrument of power in this

long, long battle against racism."

Brant did not begin writing until 1981, when

she was forty years old. The story of how Brant came to begin

writing is significant to another theme found in all her

writings: being Native. It speaks to her Mohawk heritage

and, on a larger scale, her respect and beliefs in the

connectedness of land, spirit, people and animals. Brant tells

the story in the essay "To Be or Not To Be Has Never Been the

Question," which also appears in Writing as Witness:

Essay and Talk (1994). It is well worth repeating in depth.

According to Brant, she was driving through

Iroquois land with her partner, Denise. As they were driving, an

eagle "swooped in front of our car... He wanted us to stop,

so we did." Brant then got out of the car and faced Eagle: "We

looked into each other's eyes. I was marked by him. I remember

that I felt transported to another place, perhaps another time.

We looked into each other for minutes, maybe hours, maybe a

thousand years. I had received a message, a gift. When I got

home I began to write."

Brant was published the same year she began

writing, an incredible accomplishment as any writer who wants to

be published would recognize. The accomplishment is made

somewhat more incredible by the fact that Brant dropped out of

high school at the age of 17, so therefore does not have the

"advantage" of a traditional Euro-American education. But

any lack of "proper training" is more than made up for in

Brant's abilities as a writer. Her "gift," as she calls it, has

won her several awards and honors. In 1984 and 1986, Brant

was awarded grants from the Creative Writing Award from the

Michigan Council for the Arts. The Ontario Arts Council awarded

her a grant in 1989. She was honored by the National Endowment

for the Arts in 1991. In 1992 Brant earned an award from the

Canada Council Award in Creative Writing.

Brant is multifaceted, both as a person and as a writer. As a

person, Brant is identifiable as a Mohawk Indian, a lesbian, a

mother, a grandmother, an activist, and a feminist. When Brant

dropped out of high school at the age of 17, it was to marry.

She had three daughters and then became a grandmother. Her

marriage ended in divorce after fourteen years. In another essay

in Writing as Witness: Essay and Talk called "Writing

Life," Brant describes her marriage as being lived out "in

anger, violence, alcohol, hatred." The marriage was very

abusive.

In 1976, Brant met Denise Dorsz, the woman who

was to become her partner. As of 1994, Brant and Dorsz had been

together for eighteen years. In the essay "Physical Prayers,"

which also appears in Writing as Witness: Essay and Talk,

Brant offers a glimpse into her own discovery of being lesbian:

"In my thirty-third year of life I was a feminist, an

activist and largely occupied with discovering all things

female. And one of those lovely discoveries was that I could

love women sexually, emotionally, and spiritually - and all at

once." Brant goes on to write that being lesbian makes her a

more complete person, "and a whole woman is of much better

use to my communities than a split one."

Brant is as complex of a writer as she is a

person. As a writer, Brant is the author of poetry, short

stories, essays, and critical essays, in addition to being an

editor, speaker, and lecturer. Brant's first book, Mohawk

Trail (1985), is a collection of poetry, short stories and

essays - many of which are autobiographical. Brant's second

book, Food & Spirits (1991), is a collection of short

stories. As is the case with Brant's other works, the main

characters in these stories are all Native, with most being

women - and all facing adversity in one form or another.

In 1994, Brant published another collection,

Writing as Witness: Essay and Talk. The contents of this

book include essays and writings that are based on (or were the

basis of) speeches or lectures she has given. It is in this

collection of writings that the themes, style, and issues most

important to Brant are well represented. Several of the essays

and "talks" from the book have been mentioned throughout this

essay. Other writings in the book include the essay "Anodynes

and Amulets." Here, Brant discusses racism through the

exploitation of Native American spirituality. The essay is a

criticism of the "new-age" religion, which Brant suggests has

stereotyped/idealized Native Americans, in addition to

"borrowing" some Native spiritual aspects. Brant writes, "I

long for a conclusion to the new-age religion, and in its place,

a healthy respect for sovereignty and the culture that makes

Nationhood. We do not object to non-Natives praying with us (if

invited). We object to the theft of our prayers that have no

psychic meaning to them." In short, Writing as Witness:

Essay and Talk captures the essence of Brant and her work.

In addition to her own writing, Brant has also

been the editor of several books and collections. As an editor,

Brant is known for her groundbreaking achievement for the book

A Gathering of Spirit: A Collection by North American Indian

Women, first published in 1984 as a special issue of the

periodical Sinister Wisdom, then published in book form

in 1988. A Gathering of Spirit was the first anthology of

its kind. It involved all Native American women - from

contributors to editor - and it brought Brant national

recognition. Other editing projects for Brant produced another

collection of Native writings in I'll Sing Til the Day I Die:

Conversations With Tyendinaga Elders (1995), and an issue of

the annual journal Native Women in the Arts: Sweetgrass Grows

All Around Her (1996), co-edited with Sandra Larounde.

In addition to her own publications and editorial projects,

Brant's poems and stories have appeared in a wide range of

books, such as Living the Spirit: A Gay American Indian

Anthology (1988), Best Lesbian Erotica 1997 (1997), a

new book edited by Linda Hogan, Deena Metzger, and Brenda

Peterson, Intimate Nature: The bond Between Women and Animals

(1998), as well as in numerous magazines, periodicals, and

other anthologies that are Native, feminist, and/or lesbian in

content.

The opening quote for this essay captures much

of what Beth Brant and her writing are about. Brant is able to

take her complexities as a person and turn them into honest,

straightforward writing that comes in several forms: stories,

poems, essays, short stories, even lecture notes. Her themes are

often about Native peoples, women, lesbians and gay men, and

family, and she often addresses issues such as racism and

homophobia with a directness that cannot be ignored.

There is one more aspect of Brant's writing

that has not yet been discussed here. It is the idea that words

are sacred. In the Preface to Writing as Witness: Essay and

Talk, Brant begins by writing, "In putting together this

collection... I hope to convey the message that words are

sacred... because words themselves come from the place of

mystery that gives meaning and existence to life." Brant not

only believes words are sacred, but in the essay "Writing

Life," she states that writing is medicine: "I was able

to use writing to heal a wound that was very deep and festering.

I was angry - writing brought me calm. I was obsessing about the

past - writing gave me insight into the future. I was in pain -

writing cooled the pain..." To Brant, words are sacred, and

writing is healing. These are fitting sentiments for a person

who was instructed by an eagle to write.