|

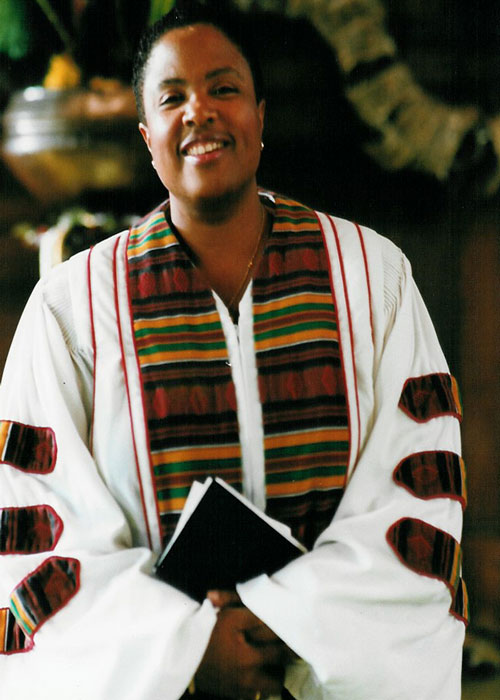

Reverend

Yvette A. Flunder Reverend

Yvette A. Flunder

Founder & Senior Pastor

City of Refuge

Community Church

Reverend Yvette A. Flunder was born in San

Francisco, to a family who were pioneers in the Church of God in

Christ. At 13, she attended Saints Academy in Lexington,

Mississippi and started her first ministry by organizing the

Campus Ministry. A graduate of Armstrong College, Reverend

Flunder became a foster parent in her early 20's and later

established a group home for high risk teens.

In 1979, Reverend Flunder began her work with the elderly

population and moved into providing direct services by

developing a variety of social services for the elderly in

residential housing. Her work in this arena received many

awards, including the Award of Excellence and the Mayor's Award

from the City and County of San Francisco.

In response to the epidemic of HIV/AIDS, Rev. Flunder, along

with other members of Love Center Ministries, established An Ark

of Love, Inc. which opened The Ark House, a communal living

facility, the first of its kind to be run by an African-American

church in Northern California.

Moving to San Francisco in 1991, Reverend Flunder founded the

City of Refuge Community Church in order to unite a gospel

ministry with a social ministry. Preaching a message of action,

the church has experienced a steady numerical and spiritual

growth in its new building at 1025 Howard Street from 50 at its

first service to over 600 member in four years. On April 30,

1995, City of Refuge Community Church made a covenant with the

Protestant denomination United Church of Christ.

Responding once again to the needs faced by the HIV infected

clients, Reverend Flunder and her staff opened the Hazard-Ashley

House in Oakland and the Restoration House in San Francisco

through the Ark of Refuge, Inc., an HIV specific non-profit

agency whose purpose is to provide housing, direct services,

education and training for persons affected by HIV/AIDS in the

Bay Area. Restoration House is a dual-diagnosis residential

facility for African-American women and the first of its kind in

San Francisco.

Reverend Flunder has received numerous awards for her work in

the HIV/AIDS field including:

|

Minsitry of the Year, AIDS National

Interfaith

|

|

Commendations from the Alameda County Board

of Supervisors

|

|

Highland Hospital Chaplaincy Program and

the San Francisco Muslim Community

|

Presently, Reverend Flunder serves as:

|

Executive Director of The Ark of Refuge,

Inc.

|

|

Co-Chair of the National African-American

Church Caucus on AIDS

|

|

Chairperson of the African American AIDS

Coalition of Alameda County

|

|

Founding Member of the African-American

Interfaith Alliance on AIDS

|

|

Member of the Alameda County Ryan White

Consortium

|

|

Member of the California Ryan White Working

Group.

|

|

President of the City of San Francisco

Parks and Recreation Commission

|

|

Chairperson of the Black Adoption Placement

and Research Center

|

WHO

IS THIS PREACHER? WHO

IS THIS PREACHER?

REV. DR. YVETTE FLUNDER

My voice is rooted in the African American

Southern Pentecostal Church where passion for God in Jesus is

heard and seen in the songs, preaching, dancing and daily

at-home meditations. I have struggled with the church and the

Bible, but not with the freestyle celebratory worship of the

Pentecostal Church. My struggle has been with the Christian

Church’s position regarding the treatment of women, homosexuals,

war, people of color and slaves (My grandmother, Bessie Hamilton

born 1895, was the daughter of Stella Wyatt who was born a

slave). I am an avowed womanist, and a reconciling liberation

theologian who dances in the Spirit and speaks in tongues.

Holding on to Jesus in spite of the church and the tortured

interpretations of scripture used to mortally wound my faith,

has been a life long journey. Finding my way, following the

Light, refusing to believe Jesus didn’t love me; this is the

foundation of my preaching. I am a desperate preacher who knows

personally how theologies are fluid and new ones are born at

friction points.

Mine is a voice that passionately preaches justice and freedom

with responsibility; however not to the exclusion of Jesus.

Justice without Jesus will not work for me.

I preach to a desparate people, who are struggling to make sense

of their lives on the margins of society. They are my beloved.

In my community, you must find God in the struggle for equality,

parity and justice; the struggle is the long, strong, deep,

resonant base of all we preach, sing and pray about. 'Through

many dangers toils and snares’...is foundational to our worship,

and the locus of our passion. If we cannot see God in the

struggle and believe day after day that God will make it all

right, then we cannot see God at all. This is the starting

point.

I preach faith based sermons to build self-worth and self-value

in the lives of people who have often been stripped of all that

is right and good. I strive to see peace and a sense of security

present in the lives of those I pastor, preach to and serve.

Emil Thomas said that, “our slave ancestors had a basis for

calm: a special inner peace born of a profound conviction that

their self worth had been well established already and was

guaranteed by the Ruler of the universe”. This is a peace born

from the assurance that God will come through for us; God is on

our side. This is what I believe; this is what I preach.

PREACHING INFLUENCES

I identify with Craddock in his book Preaching because his

approach to preaching/ teaching is very Bible, Jesus and God

centered. I’ve seen the methods he recommends for sermon

structure used both in the United Church of Christ and in the

churches of my youth; however what flows out of his center is

scripture based preaching with other sources used to support the

scripture. While I am not in total agreement with the extent to

which Craddock lifts up the authority of the Bible, I do

appreciate and believe strongly in scripture based, Christ

centered preaching for liberation. This kind of preaching

requires much study with an eye to taking Jesus back from the

fundamentalists, but it is the most effective kind of preaching

for my community. I, like David Buttrick would argue “for a

church animated by the Gospel, rather than a church heavily

under the rule of an imposed scriptural authority” , but people

who have for generations been abused by the preaching of the

Bible need to hear the Bible preached in ways that affirm and

validate them.

Craddock lifts up the need to study, to listen in silence and

reflect, and to attend to structure, form and delivery. He also

asserts that preaching is both learned and given; the learning

is the ‘how to’ method in his book, the given is the content or

core of our preaching...the Word of God. The words come from us,

the Word comes from God. I agree that when our words are

empowered by the Holy Spirit, positive change takes place, both

in the preacher and the listener.

According to Craddock, the preacher must also have good moral

character , as preaching is not just another vocation; it

assumes to give to the listener revelation from God and as such

carries great responsibility. The position of preacher is a

lofty one in my community, with equally lofty expectations.

There is a need, says Craddock, for the preacher to be sensitive

to the needs of the listener i.e. sermons should speak for as

well as to the congregation, the Gospel is from the community as

well as to it. He expresses the need for honesty and intimacy,

and the importance of preaching about things that are familiar

to the listener. Preaching in my tradition uses life experience,

or what I call ‘personal transparency’ to identify with the

experiences of the listener.

Craddock says preaching should include something people can

recognize, even in the introduction of new truths…”A

rearrangement of the familiar can make it as interesting as the

new yet satisfying as the old…present the familiar with interest

and enthusiasm”. Craddock also talks about identification or

being genuine and not exaggerated or artificial in presence or

preaching. He seems to be encouraging the preacher not to simply

be profound but to seek to be a profound blessing, by hearing

from God and paying close attention to ‘voice’ of the listening

congregation. I believe that in order to genuinely be a blessing

to the congregation the preacher must seek to know and

understand who she/he is preaching to. Lenora Tubbs Tisdale in

Preaching as Local Theology and Folk Art calls this ‘Exegeting

the Congregation’. Tisdale says, If we as preachers are going to

proclaim the Gospel in ways capable of transforming

congregational identity, we first need to become better

acquainted with the ways our people already imagine God and the

world. If we are going to aid in the extension of myopic vision

or the correction of astigmatic values then we must first strive

to ‘see’ God and the world as our people do.

It is through this synergistic relationship that the preacher

and the congregation become one organism, worshiping God

together. The preaching and the response are then filled with

faith, passion and power. This is preaching, as I understand it.

My preaching is greatly influenced by my grandfather, my father,

my uncles, my mother and my grandmother all of whom are/were

preachers. I spent my youth as a pastor’s kid in the Church of

God in Christ, a predominately Black Pentecostal denomination.

My style of preaching echoes the preachers who surrounded me,

both in my family and throughout the organization. Most of the

preachers I knew were blue-collar folk who came to their role as

preacher and or pastor without the benefit of formal training.

There were not many African Americans in college, and if they

were in school they were seeking a way to make themselves more

eligible for jobs. The call to preach was not often planned as a

vocation. It sort of ran up behind you and tackled you while you

were trying to get ahead in life. Authorization for ministry

came from the Church at such time as it was determined one was

ready. “Ready” meant having demonstrated faithfulness and an

ability to preach. The Church of God in Christ believed that no

matter how educated or filled with deep knowledge a person was

that knowledge had to be evidenced by good preaching for a

preacher to gain affirmation from the Church. Good preaching

meant good performance that included choosing a good text, a

good reading of the text, good entertainment,

believability/authority, identification, food for thought,

power, humor, passion and a super celebration. I know that

Craddock’s statement; “Listeners tend to lean into narratives

which have emotional force, but which are presented with

emotional restraint“ is an indication that we come from

different cultures. Emotional restraint was not exercised

particularly at the close or celebration time in the sermon. I

tend to agree with Frank A. Thomas, regarding celebration and

emotion. Thomas writes, “It is precisely because so much of

Western preaching has ignored emotional context and process, and

focused on cerebral process and words, that homileticians most

recently have struggled for new methods to effectively

communicate the Gospel” . The preaching was central to the

worship experience; it was the highlight. All things lead up to

it and out from it. It was a Word from the Lord.

I am fascinated when I read books like Speaking from the Heart

which detail the method often present in black Pentecostal

preaching and lift up that method as an example of how good

preaching is accomplished. I find myself often wishing that my

Grandpa Eugene (Bishop Eugene E. Hamilton) and my Uncle Rudolph

(Bishop S. Rudolph Martin) could have lived long enough for me

to share with them the fact that a science is being taught that

captures what they did among us for many years. They did not

adhere to any particular preaching calendar or use many sermon

helps written by others but the power of their sermons lives on.

Of particular interest, is the ‘science’ and skill I now

recognized in the preaching I grew up around; I know most of

those folk did not realize what masters they were in the art of

using illustrations, simile, or hyperbole, but all these thing

were part of their preaching process.

Storytelling, speaking in hieroglyphics and word pictures were

methods employed to leave a lasting impression on the hearer.

You could see it, taste it and feel it while they preached. My

Grandpa lived his sermons so his ethos and personal conviction

came through with the great passion, energy, and emotion.

The Pentecostal preaching influence is one where the language is

ordered, the lines are metrical and poetic and the sermon is

‘sung’, in places with the help of the congregation and the

musicians. This form of performance art entertained the

congregation while driving home the truths in the sermon.

Engaging the audience in a call and response to both the meter

and the message encouraged the congregation to not only

participate but it signaled that the sermon was successful.

Preaching as performance art was and is an essential part of the

African American Pentecostal worship experience.

PREACHING ON THE EDGE

As to the content of my sermons, I often preach sermons to

raise the consciousness of those who feel they have exclusive

rights to Jesus and to empower oppressed people to take their

place at God’s ‘welcome table’. I preach to build faith and to

demystify success for oppressed people. I do not consider my

preaching adversarial or divisive. As I mentioned earlier I call

myself a ‘reconciling, liberation theologian’, and my desire is

to see harmony in the Body of Christ.

Empowerment and liberation are consistent themes in my

preaching. Marginalized people often ask, “Is God for us?”

Incarnational liberating preaching is vital in these

communities, as preaching has often been used to push oppressed

people more and more to the margin. The preaching in the

community evidences the extent to which the community is

welcoming. After a natural disaster, people come to church in

record numbers asking, “Is God for us?” and then they listen for

the assurance from the pulpit. In marginalized communities

crises is a way if life and incarnational preaching is

essential.

Preaching to people who are on the edge of society and the

mainline church must have good content and good form. Preaching

to marginalized people must be believable, powerful and

passionate. Marginalized people frequently have a memory of

strong words from the pulpit used to destroy. They need stronger

words of affirmation and inclusion. In my sermons I attempt to

carry a message that counters the teaching of those who support

a theology that calls anyone unclean or claims to have exclusive

‘truth’.

TOWARD A TRANSFORMING MOMENT

I believe there must be a relationship between loving and

knowing God, the text and the people the text is shared with.

When the interpreter of the text begins by incorporating

integrity, relatedness and faithfulness to a relationship with

God and to the text there will be a more honest relationship to

the congregation/listeners. Additionally preachers must be

secure in their relationship with God and witnesses of the truth

of the Gospel. Oppressed people seem to be particularly aware

when there is disparity between what the preacher says and what

she/he really believes. Ward asserts, “If you do not have a

secure sense of self and conviction about your right to address

your people, then it will be nearly impossible to engage them.”

Marginalized people are people that need to hear from God. How

can they hear without a preacher? And the preacher must love

God, love the text and identify with the people in order to be

authentic.

When these things come together I believe we achieve what

Bozarth calls the moment of ‘transformation’. I seek for this

moment in my preaching. I have no greater joy than to embody a

liberating truth and to participate in the circle dance as the

Holy Spirit brings life to me and to those that hear and receive

the Word. God in Christ through the Holy Spirit empowering the

preacher and the congregation through the embodied Word …The

circle is complete, and the kingdom is revealed. It is a glimpse

of heaven.

PART II

Mitchell, Henry H. and Thomas, Emil M. 1994. Preaching

for Black Self-Esteem. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 133

Craddock, Fred B. 1985. Preaching. Nashville: Abingdon

Press, 27

Buttrick, David. 1994. A Captive Voice: The Liberation of

Preaching. Louisville: John Knox Press, 30

Ibid., 23

Ibid., 26

Ibid., 160

Ibid., 165

Tisdale, Lenora Tubbs. 1997. Preaching as Local Theology and

Folk Art. Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 57

Craddock, p.164

Thomas, Frank A. 1997. They Like To Never Quit Praising God:

The role of Celebration in Preaching. Cleveland: United

Church Press, 5

Ward, Richard. 1992. Speaking From the Heart: Preaching with

Passion. Nashville: Abingdon Press, 48-49

Bozarth, Alla Renee. 1997. The Word’s Body: An Incarnational

Aesthetic of Interpretation. Lanham,MD: University Press Of

America, 116

Source:

http://www.sfrefuge.org/

City of Refuge

1025 Howard Street

San Francisco, CA 94103

(415) 861-6130

fax: (415) 861-6103

Email:

webmaster@sfrefuge.org

|

The Ark of

Refuge

1025 Howard Street

San Francisco, CA 94103

(415) 861-6130

fax: (415) 861-6103

Email:

|

This site contains HIV prevention messages that

may not be appropriate for all audiences. Since HIV

infections spread primarily through sexual practices or by

sharing needles, prevention messages and programs may address

these topics. If you are not seeking such information or may be

offended by such materials, please do not visit this website.

|

|

|

KQED Interview

Reverend

Yvette A. Flunder

City of Refuge Ministries

[Note: If movie does not appear above, click link below to

view]

View Quicktime Movie

There's Power

Click to hear

selections

The Abingdon Women's Preaching Annual: Series 1, Year C

(Abingdon Women's Preaching Annual)

by Leonora Tubbs Tisdale (Editor)

Birthing the Sermon: Women Preachers on the Creative Process

by Jana Childers (Editor)

Can the Lord Be My Shepherd If I Am Gay?

Anderson, D. Min. , Pamelajune

|

|

|