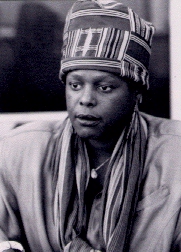

Alexis

DeVeaux

Alexis

DeVeaux

Author

"I'm interested in the relationship between

history and literature, so I like to investigate how African

American women and women of color construct our visions of

history while appropriating literary forms. I see our

contemporary literatures as agents of social change, critical to

our different but similar struggles for self-determination and

peoplehood. As a writer intimately engaged in this process

myself, I teach courses that are designed to challlenge the

dominant paradigms of history, literature, and creativity."

Alexis De Veaux is a poet,

playwright , and novelist born and raised in New York City. Her

plays include, Circles, Tapestry, and A Season

to Unravel, which was produced by the Negro Ensemble

Company in 1979. She has also published a novel, "Spirits

In The Street," and a picture book, "NA-NI." She is

currently poetry editor of Essence Magazine.† She is

an associate professor of Womenís Studies at the University at

Buffalo and has traveled as an artist and lecturer throughout

the U.S., Africa, Europe, Japan and the Caribbean.

Education:

ďI was not very settled as an undergraduate and so I started out

at Cornell and ended up at Empire State, I think, looking for

writing programs because ultimately, that is what I was really

doing in the late Ď60s to early Ď70s. When I came to Buffalo, I

had just turned 40 and I was going to graduate school. I got my

MA here, in the department of American Studies, and it seemed

like a cool thing to address underdeveloped moments as an

intellectual. And I got my Ph.D here, at UB in the department of

American Studies with a concentration in Womenís Studies.Ē

Current Project:

ďI just finished this biography of Audrey Lourde which took me

seven years to create and to manuscript. At the same time, Iím

working on some short stories and Iím also working on a

collection of essays.Ē

On her name and ďMasaniĒ:

ďIn 1986, a South African friend of

mine gave me the name Masani, which means Ďgirl-child born with

gap teeth.í So for a long time, I didnít own the name; I wasnít

really sure what I was doing. Also, I love my name. My mother

actually named me after Alexis Smith, who was an actor in the

40s and 50s who didnít quite come to fame in the way that

Barbara Stanwick or Betty Davis or Joan Crawford did. But I

never thought that I could relinquish that name, because my

mother said she wanted to name me after a tough broad. And she

was very purposeful about it. So I thought, rather than delete

that name, I would just add to that. So lots of people in the

university know me as Masani Alexis DeVeaux, and people in the

literary world know me as Alexis DeVeaux. So Iím sort of using a

number of different personas, and I kind of like that.

Whatís it like to

have a banned book? Itís sort of interesting to be considered a

banned author, because it really to me means that youíre doing

something very right. And that you are raising issues that

people presumably donít want children to know about. So the book

is about a little girl who fantasizes about getting a bicycle

and the family is a family that is on welfare And the check is

stolen the day that she thinks she is going to get the bicycle.

Now this book was published in 1973, so back then, anybody whoís

doing stuff in childrenís literature thatís veering from the

norm is really taking a chance. The fact that it was banned

and/or presents me as a challenge, suggests to me that Iím

really on the right course.

What is your

strangest performance moment? In 1988, when I was in Japan. Not

so much because it was Japan, but because as someone whoís

really dependant upon being able to read, and therefore figure

out my life by reading, I realized that in Japan I couldnít

decipher the alphabetóitís all pictures. And so there are no

root words like in French or in Spanish or Italian you sort of

could guess at. And it was this sense of being illiterate as a

person who only spoke English that was really really strange for

me.

Most profound

mentors: If I name two, Iím going to

be in trouble. So let me say this, because I think this would be

more true: The community of black woman writers have mentored me

in different ways, I mean historically but also in a

contemporary way. I understand that as a black woman writer, I

can have any voice because there are a variety of voices within

that community. So itís that whole tradition that mentors me.

And it would be hard in that regard to say that itís just this

person or that person.

Career

highlight: Actually, there are two.

The first was in 1972, when I won a National Black Fiction

contest. It was my first short story and I entered the

conference on the last day, at the last hour, and never expected

anything from that. But I won first place. So that was a real

moment in terms of saying, ďOK, this is possible.Ē More

recently, what stands out for me amongst many wonderful moments

is that I had the opportunity to be in South Africa when Nelson

Mandela was released. In fact, I was part of a team that was

sent to South Africa in anticipation of his release. And I was

one of the first international journalists who got to interview

him. And I did an exclusive interview with Mr. Mandela and his

wife, Winnie Mandela at the time at their home in Soweto, so I

blew up from there. So that was in 1990, I think it was.

Career

highlight: Actually, there are two.

The first was in 1972, when I won a National Black Fiction

contest. It was my first short story and I entered the

conference on the last day, at the last hour, and never expected

anything from that. But I won first place. So that was a real

moment in terms of saying, ďOK, this is possible.Ē More

recently, what stands out for me amongst many wonderful moments

is that I had the opportunity to be in South Africa when Nelson

Mandela was released. In fact, I was part of a team that was

sent to South Africa in anticipation of his release. And I was

one of the first international journalists who got to interview

him. And I did an exclusive interview with Mr. Mandela and his

wife, Winnie Mandela at the time at their home in Soweto, so I

blew up from there. So that was in 1990, I think it was.

What do you do to

relax or escape? I love to watch videos... movies. Iím a real

movie freak. And itís probably because movies are stories. When

Iím really into my mode I like to bike, but now Iím walking

because the weatherís kind of in-between. I canít tell you about

my vices because this is a public moment. I canít say, like,

everything, OK? But I have good relaxation techniques.

Do you have a

preferred writing medium? Actually, no. I feel gifted, I feel

blessed that Iím gifted to move in and out of genres. And every

story has its own medium. And I know that a spirit is moving

through the work and itís taking me there. Sometimes, I think

Iím writing a poem but Iím actually writing a story and

vice-versa. I just feel like itís good to be able to explore all

aspects of your literary imagination.

First published

work: That one short story I told you about. It was called

Remember Him, an Outlaw, published in 1972 in a now defunct

magazine that was published by the Afro-American Institute at

New York University.

Do you have brothers

or sisters? I have six living siblings, two brothers and four

sisters. My oldest sister died in 1983. So I am now oldest.

On teaching: Being an Associate Professor at

UB, I think the thing I bring to womenís studies is a primary

identity as an artist as someone who is involved in culture and

cultural issues. At the same time, what I try to do is make a

relationship between literature and history. I try to look at

the intersections between literature and history. I donít think

that any book is written in a vacuum. I think itís written

within its own particular social or political moment. I think

thatís a way of doing womenís studies thatís not primarily based

on theory, but itís more empirical. Itís based on living as an

artist and living a cultural life, and bringing that to

scholarship.

†

Source:†

http://www.artvoice.com/march21_27_2002/pages/speeddialprofile.html

†