|

In Memoriam In Memoriam

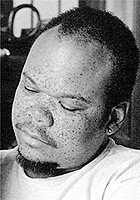

Marcelle Cook-Daniels

March 1, 1960 - April 21, 2000

Marcelle Y. Cook-Daniels, 40, died April 21 as

a result of suicide, following a lifelong battle with clinical

depression, according to his partner of 17 years, Loree

Cook-Daniels. A native of

Washington, D.C., where he lived until his 1996 move to Vallejo,

California, Marcelle was a computer programmer/analyst who

worked for the IRS, the Maryland-National Capitol Park and

Planning Commission, and, most recently, Norcal Mutual Insurance

Company of San Francisco. At the time of his death, he was

actively working toward his M.S. degree in Computer Science at

Golden Gate University.

A

quiet but very dedicated and principled activist, he was known

for his work in raising awareness of transgender and Lesbian/Gay

issues and for his efforts to promote and support his family

values of love, commitment, honesty, openness, and public

service. His education and advocacy work included presentations

at the 1999 Creating Change conference, the 1998 "Butch-FTM:

Building Coalitions Through Dialogue" event, several True Spirit

Conferences, and numerous other educational and advocacy events.

Interviews and/or photographs of him appear in the "Love Makes A

Family" book and tour; Dawn Atkin's book "Looking Queer: Body

Image and Identity in Lesbian, Bisexual, Gay and Transgender

Communities," and "In The Family" magazine. He was an active

supporter of COLAGE (Children of Lesbians and Gays Everywhere)

and provided substantial material and volunteer support to the

Transgender Aging Network, four True Spirit conferences, and The

American Boyz. A

quiet but very dedicated and principled activist, he was known

for his work in raising awareness of transgender and Lesbian/Gay

issues and for his efforts to promote and support his family

values of love, commitment, honesty, openness, and public

service. His education and advocacy work included presentations

at the 1999 Creating Change conference, the 1998 "Butch-FTM:

Building Coalitions Through Dialogue" event, several True Spirit

Conferences, and numerous other educational and advocacy events.

Interviews and/or photographs of him appear in the "Love Makes A

Family" book and tour; Dawn Atkin's book "Looking Queer: Body

Image and Identity in Lesbian, Bisexual, Gay and Transgender

Communities," and "In The Family" magazine. He was an active

supporter of COLAGE (Children of Lesbians and Gays Everywhere)

and provided substantial material and volunteer support to the

Transgender Aging Network, four True Spirit conferences, and The

American Boyz.

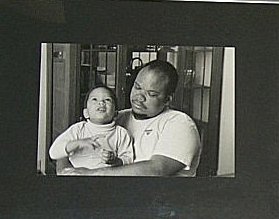

Marcelle

was at heart a family man. He was a devoted son to his mother

Marcella Daniels; a passionate supporter of his lifepartner of

17 years, Loree Cook-Daniels; and an outstanding father to his

6-year-old son Kai Cook-Daniels, who calls him, "The Best

Lego-Maker in the World." He is also survived by many beloved

friends and colleagues. Marcelle

was at heart a family man. He was a devoted son to his mother

Marcella Daniels; a passionate supporter of his lifepartner of

17 years, Loree Cook-Daniels; and an outstanding father to his

6-year-old son Kai Cook-Daniels, who calls him, "The Best

Lego-Maker in the World." He is also survived by many beloved

friends and colleagues.

My Life As An

Erroneous Sonogram

By Marcelle and

Loree Cook-Daniels

An interview of Marcelle concerning his body image and decision

to transition female-to-male.

|

L:

|

Let's

start by you describing how you think of yourself at this

point.

|

|

M:

|

I

guess the phrase that I've come to is psychological

hermaphrodite. It's the only thing that sounds like

something that's both and neither at the same time.

|

|

L:

|

Well,

if the hermaphrodite is psychological, then what is the

physical?

|

|

M:

|

The

physical is definitely more male. I think where the female

comes in is emotionally, and in my approach to life and

the world. My communication style is a little of each of

what is traditionally thought of as male and female. And

as far as relationships go, love is more important to me

than sex. But, those things are just sort of broad-stroke

stereotypes of male and female.

|

|

L:

|

I'm

curious: when I asked you about the physical, you said

that it was definitely more male. But if someone were to

see you with your clothes off, they would have no question

that your body is female.

|

|

M:

|

Now,

you mean?

|

|

L:

|

Yes.

So how do you resolve that? Or are you already living in

the future?

|

|

M:

|

I

guess I am already living in the future. I guess I've

always lived in the future. I think that's part of the

whole dysphoria. Let's use an analogy. Say you always

think of yourself as being 5'10". And in your mind, or in

your house which represents your mind, you have everything

scaled so that in relation to it, you seem 5'10". And in

your own little, safe corner, you are a 5'10" person. Your

chairs and your furniture are all proportioned to make you

look like you're 5'10".

|

|

|

Then

you go out in the world, and the world is scaled the way

it usually is, and you realize that you're 4'10". To the

world, anyway. But the way you've always thought of

yourself, the way you've thought of yourself not in

relation to other people, is as 5'10". So, I guess what

I'm doing is something akin to having my legs surgically

lengthened, so that when I go outside, people will see the

person I always see inside.

|

|

L:

|

So

you have been seeing yourself as male all along?

|

|

M:

|

Basically. It's kind of schizophrenic, I guess. My problem

is mirrors and photographs and other people. I see myself

a certain way, and then I'm faced with a "real" image that

is very different from how I am in my mind. I feel I look

a certain way in the world, am a certain way, and then

something happens that changes that. Reality intrudes.

|

|

L:

|

Can

you talk about a specific example of what might happen and

how you might feel when that reality intrudes?

|

|

M:

|

Say

I'm going out somewhere, and I'm picking out clothes and

thinking of things that would work with each other. I'm

thinking of a particular way I want to look, a particular

image I want to convey. I take all this time and dress,

and then when I check in the mirror to see how everything

looks, there are these breasts that are staring back at

me, and the shirt doesn't hang the way I thought it was

going to. In my mind's eye, when I'm seeing myself, I

don't see those. For instance, I like suspenders. But I'll

put those on, and they bow out to the side because there

are these huge impediments in the way. So I end up taking

them off.

|

|

L:

|

That's an example of when you've met with your reality

versus a different reality in the mirror. What happens

with people?

|

|

M:

|

Well,

there's the pronoun problem. I'm going out, and I think

I'm really doing a good job of passing as a man and I'll

get "ma'am"ed. Actually, sometimes it's nothing that

obvious...it's just something like going into a building,

and the guy in front of me stops to open the door for me.

|

|

L:

|

You're assuming he's doing that because you're female?

|

|

M:

|

Oh,

yeah! It's not even an assumption sometimes. Sometimes I

will stop and open a door, and try to wave the man on in

front of me and he'll stop and say, "but that's not the

way I was brought up!"

|

|

L:

|

Is it

the breasts that make you female?

|

|

M:

|

I

think that, given my other physical characteristics, it's

the breasts that are the deciding factor when someone's

waffling on the fence, trying to decide which way to take

me. They are the most noticeable, prominent feature I have

next to the freckles. Men can have freckles, but men

usually don't have breasts, and if they do they're not 42

DDDs. I try to minimize that by the way I dress and the

kind of clothes I wear, but I know that they're a focal

point. I've talked to people before, men, and they're not

making eye contact, they're looking at my chest.

|

|

L:

|

Aside

from the breasts, you think you present to the world as

fairly androgynous?

|

|

M:

|

I

think I present to the world as fairly masculine. My body

language, voice, facial expressions, I think all of those

are sort of masculinizing cues. As Kate Bornstein said in

Gender Outlaw, people are going to err on the side of male

unless there's some feminizing cue, and so far the breasts

have been the feminizing cue. I know, because I've been in

situations where I've done things like wear pretty

feminine earrings, but I've done things to conceal the

chest, and I've still gotten "sir." So even dangly

pearl-type earrings or something are not enough to

convince someone that I'm anything other than a man

wearing dangly pearl-type earrings.

|

|

L:

|

Which

came first for you, looking kind of masculine or feeling

masculine?

|

|

M:

|

Feeling.

|

|

L:

|

So

the looking masculine you've cultivated.

|

|

M:

|

Looking masculine I think I've accentuated more, to

counteract the physical presentation. It's also part of

who I am. I was always a "tomboy." Even before I had

breasts, I was always told I was acting more like a boy

than a girl. I'm just much more aware of working at the

appearance more, of having to think about it. So I don't

know what I would be like if I didn't have to

overcompensate for the physical stuff. I don't know if it

would be much different or if it's just a part of who I

am. The way I sit, the way I walk.... The testosterone

helps too with the voice, the 5 o'clock shadow, the hair

on my arms. I even have a receding hairline now.

|

|

L:

|

You

started by describing yourself as a psychological

hermaphrodite, but we've been talking "male" and

"masculine." How do you reconcile those two? Or do you?

|

|

M:

|

When

I'm talking "male," I think I'm talking about the physical

presentation. I don't know about the rest of it; I haven't

come to a decision about that. I just know that when I

think of myself after the surgery, I think of myself as

physically presenting as male, but what my identity will

be and what I really will be...I don't know that it has

any antecedent.

|

|

L:

|

So

even though other people have changed their gender

identities, you feel like you are forging new ground? A

pioneer?

|

|

M:

|

Well,

I'm not changing my gender identity; my gender identity

has been fairly constant. What I'm changing is my gender

presentation, I guess. I also don't think of myself as

being a pioneer. I'm not a follower. I'm not a leader. I'm

just doing what I have to do.

|

|

L:

|

In

Stone Butch Blues, Leslie Feinberg talked a lot about the

problems faced by people she defines as "he-shes." People

who sort of confound other people's sense of the dichotomy

between male gender and female gender. Would you say that

the "he-she" analogy fits for you, first of all, and

second, do you think you've had problems by not clearly

fitting into "male" or "female"?

|

|

M:

|

Oh

yeah. I've definitely had problems with fitting in. Take

job interviews. I refuse to wear a dress to a job

interview, because I'm not going to wear a dress on the

job. I pretty much wear pantsuits. I have no doubt that

I've gone in and people have thought, "oooh!" and not been

able to deal with me on that level...I'm too butch.

|

|

|

There

have been problems with other professionals, doctors in

particular. I've called my gynecologist's office and the

staff has said, "I'm sorry, sir, this is a gynecologist's

office," and I've said, "I know, I'm a patient, trust me."

Or, dealing with salespeople. I'll walk up to the counter

and they'll say "yes sir, er, ma'am." Then they're all

flustered and they can't deal with me. I just want to say

"pick one, it doesn't matter," and move on to the

transaction. In Leslie's definition of a "he-she," I think

that's the same thing I'm saying about the psychological

hermaphrodite. I'm not all one or the other. I can't say

how I'm going to feel two years down the road, but right

now I think I "bend" gender and probably always will. At

least, whatever percentage of my identity governs my

physical self, that percentage is predominantly what would

be considered "male".

|

|

L:

|

How

early do you think you were perceived as a "he-she" or

perceived by others as not fully fitting into the category

of "female"?

|

|

M:

|

Probably from very early. As I said, I was a pretty severe

tomboy, although I did like being around the girls better

than I liked being around the boys. So it didn't

necessarily follow a "straight" line -- identifying as

male or female and wanting to associate with the same. I

liked being a "boy" among the girls. I got a great deal of

satisfaction about that, in more ways than one. I just

pretty much thought the boys were awfully boorish. But I

almost felt like an infiltrator with the girls. I felt

like I was...that I was a pretender, that I was there in

disguise. But I was still very tomboy-like, very physical,

very daring. I did lots of climbing, rough- and-tumble

type stuff. Also, I had a romantic interest in girls which

is pretty common for a baby dyke. The girls were more

willing to play "doctor" with one of their own than with

the boys, so I got a lot of mileage out of that. The

problem came in when I hit puberty. All of a sudden,

inside of weeks, I started getting breasts, which were

totally wrong, in my opinion. They got in the way. And

they drew attention to me as a girl. People started

saying, you're growing up, you've got to stop all these

tomboyish activities. I was not about to stop. I didn't

want to. Beyond that, I knew it just wasn't right. What

was happening was just not me.

|

|

L:

|

The

physical changes?

|

|

M:

|

Yeah.

Up to that time, I was fine. Up until age 11, I had a flat

chest, and I was fine. I had to deal with the period and

what that meant, but by itself, that wasn't bad. That was

hidden, so it wasn't a big deal. But the breasts were very

noticeable, very out there. And very damaging to my

self-image.

|

|

L:

|

If

you could have had smaller breasts, would you have had an

easier time, you think, staying in the female gender? Or

settling into it?

|

|

M:

|

I

don't know that that's true. I think if I had smaller

breasts, I would've tried passing more often, earlier. I

would've tried to pass altogether. I don't know that it

would have made that much of a difference. I think I would

have come to the same decision sooner or later. I think it

would have just allowed me to pass more easily.

|

|

L:

|

Let's

shift the conversation a little and talk about images of

beauty. How does either the body you have that the world

sees now, or the body you see in your head, relate to the

images of beauty or attractiveness both in the society at

large and in the Lesbian/Gay community? How does

attractiveness figure into all this?

|

|

M:

|

I

don't think of myself as an attractive woman. I just don't

think I do "woman" well. I'm definitely far outside the

mainstream beauty image. I've tended to play up the

Lesbian butch image, but I don't know that I necessarily

fit that either. When I think of Lesbian butch I think

white. More specifically, I think somewhat tall or medium

height, short hair, handsome features, Caucasian. I'm kind

of pudgy, lumpy, big-breasted. I don't think I fit either

straight or Lesbian. I think the straight ideal of female

beauty is pretty narrow; very few women fit it.

Admittedly, the body I see in my head leans more toward

the masculine attractiveness ideal. I would like to be

trim and fit and well-muscled, which to a degree I already

have because I do have a muscular body that can be

developed even more on testosterone. But again, even the

gay male ideal or the straight ideal for men -- I don't

think I fit that either. One, I'm too short. And two, I

tend to think of that ideal as being white, also.

|

|

L:

|

So

the fact that you're perceived as black almost by

definition meant that you couldn't have been seen as

attractive as either a male or a female?

|

|

M:

|

No. I

wouldn't say not seen as attractive, but not the ideal,

which as I said, fits very few people in this society. I

have no doubt that some people may find me attractive, I

think more so as male than female, but those would be

people who don't necessarily accept society's view of

ideal beauty. But even as a black, I don't have classic

features. My complexion is too uneven. It would be better

if I was all chocolate-brown, or all-tan, but not

necessarily the mix that I have with the freckles. But

other than that, I don't think I'm totally unattractive. I

tend to think of my appeal as being somewhat

idiosyncratic.

|

|

L:

|

So

being black has affected your images of beauty. Has being

black had any affect on how you see gender?

|

|

M:

|

Yes,

I think it has. In the back of my mind I always knew that

gender realignment would make me a black male in a society

where black males are tolerated at best, and hated and

feared at worst. That bias is something I have to get away

from myself. I haven't had a real high opinion of most

black men. I think of the exaggerated macho, fathering

babies and abandoning them, that kind of thing. I think if

anything, it's stood in my way of accepting my maleness.

|

|

L:

|

It

would have been easier for you to have the feelings you

have about your gender if you had been white...

|

|

M:

|

Oh,

definitely!

|

|

L:

|

...because it would've been easier to imagine yourself as

a white man than a black man.

|

|

M:

|

Most

definitely. You and I have talked about television images

and, in particular, [the TV show] Mod Squad before. I

didn't identify with Link so much as I did with Pete. So I

think it would have definitely been a lot easier to

accept. But I gave up on being "white" when I was a kid. I

didn't want it anymore.

|

|

L:

|

Given

all that, when you're in that in- your-mind-"house" we

talked about earlier, are you seeing yourself as a black

male or a white male?

|

|

M:

|

Actually, I see male of indeterminate race. I see a

mixture. Brown-skinned, decidedly, but mixed.

|

|

L:

|

But

that's not necessarily how you define yourself out in the

world, is it, brown- skinned and mixed?

|

|

M:

|

Well,

I'm leaning more towards it. When I filled out a survey

recently, they had a question about race. They had

African- American, European-American, Asian- American,

Native American, Other as choices. I put down "Other," and

in the space for "Other," I wrote down African- American,

European-American, and Native American. So, I don't know,

maybe that's what I have to do now to accept the male:

somehow downplay the "black" part.

|

|

L:

|

Because it's too scary to be a black man in this society?

|

|

M:

|

Maybe. Or maybe because I'm challenging what is male and

female and whether one has to be one or the other, and

that's making me wonder about all the categories. I don't

know, really. My guess is it's probably a mixture.

|

|

L:

|

When

we were talking about images of beauty, you talked about

being pudgy. When we met, you were not pudgy. You'd lost a

lot of weight and had worked out and were in very good

physical shape. You were also taking testosterone and

getting ready, to some degree or another, to go through

with surgery. Over the years since, you began putting on

weight and got out of shape. In retrospect, those were the

years in which I blocked you from going forward with the

surgery. Do you think there is a connection between your

weight gain and being kind of "stuck" in being female?

|

|

M:

|

There

is definitely a connection. That's funny, I was just

thinking about that today. I was retracing the timeline. I

think I stopped taking the hormones in '86, and I think it

was right after that time that I started really porking

out again. Looking back, I think I had an investment in my

body before then. I started my weight loss program and

everything when I was around 17, when I had decided that I

was definitely going to go through surgery, this was what

I wanted. I started to work out, and lose weight. Then

when I was about 18 or 19, I started taking the hormones.

At that point I also started to develop other physical

characteristics I wanted: the growth of body hair, and

then the voice deepened, and I became more muscular. My

body was starting to be shaped more and more the way I

wanted it to, and I started to take more care of it and

appreciate it more and like it more. Then after we got

together and it became clear to me that I wasn't going to

be able to go through with it [surgery], I stopped taking

the hormones because I just figured, "why? Why bother any

more?" I started to lose that investment in my physical

appearance again, and I just didn't care any more. I've

noticed now that I've started to feel a little more like I

care what I look like. Now I have a little more investment

in my body. Unfortunately, it's a little harder now to get

in shape than it was when I was 17!

|

|

L:

|

One

reason it may be a little harder is because now you've had

a baby. Can you talk about what it was like, as someone

who's dealing with gender issues, to try to get pregnant,

and then being pregnant?

|

|

M:

|

Originally, I had decided to be the one to carry the child

because I thought that it would help me "be in my body,"

that it would help me "ground" myself in my female body. I

thought the experience would make me accept the way I was

more, so that I wouldn't have to keep dealing with the

gender stuff. It didn't turn out that way.

|

|

|

Getting pregnant was so goal-oriented, I don't know that I

thought about it much. BEING pregnant was interesting.

Being pregnant felt almost like there was some kind of

parasitic creature in me. It didn't feel real, somehow. It

just felt like some strange thing controlling my emotions

and my body, and making me eat when it wanted to. If I

didn't eat enough, it took all my energy and I didn't have

any left. And just the movement inside, and all that....

It was very ungrounding as opposed to grounding. I

dissociated a lot from my body. I wasn't able to deal with

the experience in a positive way. I was sick all the time,

and tired, and in pain. I definitely think part of that

was the idea that I was a pregnant woman. And the more

people paid attention to that, the more pissed-off I was.

I didn't even want anybody at work to know until

absolutely the last minute.

|

|

L:

|

Talk

a little bit, if you can, about how it felt when people

reacted to you as a pregnant woman, either people on the

street or people you knew.

|

|

M:

|

Well,

I don't think very many people on the street ever related

to me a pregnant woman because I didn't do the "pregnant"

stuff: I didn't dress pregnant, I didn't walk pregnant --

as far as I can tell -- I didn't act pregnant. At work,

when it all came out, I had all these people walking

around giving me unsolicited advice: [falsetto voice] "Oh,

well, you've got to do this and you've got to do that and

now you've got to breastfeed and this, that, and the

other." All of a sudden everyone was in my business, and

in my business about this in particular. People telling me

what I should and shouldn't do: I shouldn't be lifting

that, I shouldn't be doing this. And as a butch, the

actuality was, I was functioning at a lower level and I

couldn't do many things. I couldn't lift stuff, I couldn't

reach for things, and I had no energy. So, my whole butch

self- image which I'd cultivated all this time got really

out of whack. The care people were giving me, making sure

they carried things for me, opened doors for me -- it made

me very angry.

|

|

L:

|

You

breastfed the baby for awhile. Given how much upset your

breasts have caused you all your life, was breastfeeding a

problem?

|

|

M:

|

That's another way the dissociation came in. I didn't

really think of them as my breasts so much as the source

of his food. They ceased to become, in lots of ways, a

part of my body. It was just sort of his meal, that's the

way I looked at it. I wouldn't bear my breasts in public

in order to breastfeed, but I get uncomfortable when other

women do that, too. I really, at least I think I did, did

a good job of separating myself from what was happening.

|

|

L:

|

The

baby we were expecting based on sonograms was a girl.

That's what we were prepared for. And then when you had

the baby, it turned out to be a boy. Given your gender

issues, what did it mean to you immediately and then later

to have a boy?

|

|

M:

|

Well,

the first time I heard he was a boy, I was coming out of

the anesthesia [from a C-section] and I refused to believe

them. I think I asked them about four times: "What did you

say it was again?" "A boy." And I was like, "Oh, well how

did that happen?" So there was shock. But I was also just

plain relieved that it was over and he was here, and in

some ways it didn't really matter that it was a boy. There

was a little bit of disappointment. I was struck,

actually, by what I took as sort of a metaphor for my

life: We thought our child was a girl, and prepared for a

girl, we had a girl's name picked out, and were all ready

to receive this female, and it turned out to be a male! I

thought about that as a metaphor for my life in that by

all appearances -- my life being the erroneous sonogram --

I was a girl, but surprise!, I wasn't; I was a boy. Very

early, within a few hours, I remember thinking, well, I

wonder if his is a message. That this means I'm supposed

to go through with it [gender realignment].

|

|

|

Later

I started dealing with my disappointment in the fact that

he wasn't a girl. I had to examine my feelings about males

in general and my feelings about my being male, or my

maleness.... I realized that I had to do some work to

accept him being male, and that was the same work I needed

to do to accept me. So in lots of ways, Kai's gender was

another positive push.

|

|

L:

|

When

you say you have "to do some work" to accept Kai's and

your maleness, what do you mean?

|

|

M:

|

I had

to start thinking, well, what is it...what are the

problems I have with men in this society? And how much of

those problems stem from the way males are socialized, and

how much is irrevocably "male"? And so I had to sort of

broaden and loosen my thinking about what males were and

females were, and what they are capable of. I had to start

looking at more of the paths or, sometimes, the lack of

paths, that we're given to pursue based on perceived

physical limitations, gender, height, or color, or any

other sort of arbitrary means of measuring people. So I

think it is in lots of ways making me less rigid about why

people are the way they are, and how much of that is

intractable -- how much of that is biological -- and how

much of that is sociological -- how much we buy into the

system.

|

|

L:

|

Given

that, what do you think your transgender identity is going

to mean for Kai? What are your hopes and fears about that?

|

|

M:

|

I

don't really have a lot of fears. Hopes are that he won't

be so rigid in his gender expectations. That he might be

more capable of seeing people as people, and that he might

be able to see degrees of maleness and femaleness and

"otherness." And, hopefully, he'll be able to see that

being a male or being a man has very little to do with

just the physical, that it's a whole package that has to

be developed. I mean, most people just kind of go through

life saying, "I am what I am." They don't have to think

about what they are, and what it means to be what they

are. And I would hope that, given my experience, he would

be more self-aware, and more self-examining about who he

is and what he is, and why he is what he is. Just make him

a much more conscious person in general. Not take things

at face value.

|

|

L:

|

What

are your hopes and fears about what will happen to you

when your surgery is complete and your papers are changed

and everyone has accepted you as male?

|

|

M:

|

Well,

I do fear that I'll be perceived as "selling out."

Regardless of what some people think, this is not about

male privilege. That's something else that I had to fight

in myself all along -- am I doing this just because men

supposedly have it better in this society? That's another

realization I had to come to. No, I don't necessarily

think men have it better. So my fear is that people will

assign the wrong motives to what I have done, and make

certain assumptions about me based on those motives. That

they may, for instance, think that I think being a woman

in this society is so awful that I couldn't do it, that I

had to cop-out. Although they do that now...make

assumptions about me based on my perceived gender, or my

sexual orientation, or my color.

|

|

|

My

hope is that I will be able to live openly as a

transsexual or transgendered male, be up front about that

and have people accept me for that, and not try to make

assumptions about who I am.

|

|

L:

|

So

what are your motives?

|

|

M:

|

My

motives are just to have my...to have things in synch. I

don't know how else to put that. I don't believe that when

I have the chest surgery in late August, that there are

going to be any really profound, immediate effects on my

life. I mean, I'm not going to be suddenly richer, or

handsome, or anything like that. I just feel I'll be more

at peace with who I am, and more happy with the way I am.

That's the whole point in going through all this. As for

any long- term effects, changes...I'll just have to see as

I go along. I can't really say what the future will hold.

I just know it'll be better.

|

Source:

http://hometown.aol.com/marcellecd/Erroneous_Sonogram.html

http://hometown.aol.com/marcellecd/Transgendered.html

|

|

|

Articles by Loree Cook-Daniels

Transgendered? by Loree Cook-Daniels

Transgendered can mean many things.

For a general discussion of some of the terms, read this article

from American Boyz's publication.

"Femmes,

Butches and Lesbian-Feminists Discussing FTMs" by Loree

Cook-Daniels — What are the ethics of non-trans people

discussing trans identities? This essay poses a series of

questions to help move the discussion in ethical directions.

"Birthing

New Life" — An essay by Loree Cook-Daniels on Marcelle's

pregnancy, the birth of our son, and Marcelle's decision to

transition. A version of this has been published in Mary

Boenke, ed., Trans Forming Families: Real Stories About

Transgendered Loved Ones (Walter Trook Publishing, 1999)

"Body

Parts" — An early essay by Loree in which she

understands that her fears about Marcelle's transition have more

to do with her than with Marcelle.

"Trying

to Keep the Boats Together" — A "Common

Ground" column on why we shouldn't be dividing the "T"

from the "LGB."

"Life

Stories" — What kind of paths do female partners of FTMs

take through transitions?

"TransPositioned"

— A nonfiction article on the issues facing lesbians when their

partners transition FTM.

Read the fantastic

keynote address Loree delivered at the 2000 True Spirit

Conference!

Growing Old Transgendered

by Loree Cook-Daniels

Are FTMs who have been on testosterone for 30 years more likely

to develop blood problems? Are there heart medications they

should steer clear of? Is 65 too late to have a phalloplasty?

Nine months later, a difficult rebirth has begun -- By

Loree Cook-Daniels

A Letter to Marcelle

|

|

|