Honorable Mention Honorable Mention

A'Lelia Walker

Full name, Lelia

McWilliams Robinson Wilson Kennedy; born June 6, 1885, in

Vicksburg, MS; daughter of Sarah Breedlove (founder of a

hair-care products company; later known as Madam C. J. Walker)

and Moses McWilliams; married a man named Robinson (divorced,

1914); married Wiley Wilson, (a doctor), 1919 (marriage ended);

married James Arthur Kennedy (a doctor), early 1920s (divorced,

1931); children: Mae Bryant Perry. Education: Attended

Knoxville College, early 1900s.

Walker was born in

Vicksburg, Mississippi, grew up in St. Louis, Missouri, and

attended Knoxville College in Tennessee before going to work for

her mother, Madame C.J. Walker (Sarah Breedlove Walker), who had

made a fortune in the hair-care business. When her mother died

in 1919, Walker inherited the business and the lavish family

estate, Villa Lewaro, in Irvington, N.Y.

Certainly the most opulent

parties in Harlem were thrown by the heiress A'Lelia Walker.

Walker was a striking, tall, dark-skinned woman who was rarely

seen without her riding crop and her imposing, jeweled turban.

She was the only daughter of Madame C. J. Walker, a former

washerwoman who had made millions marketing her own

hair-straightening process. When she died, Madame Walker left

virtually her entire fortune to A'Lelia. Whereas Madame Walker

had been civic-minded, donating thousands of dollars to charity,

A'Lelia used most of her inheritance to throw lavish parties in

her palatial Hudson River estate, Villa Lewaro. and at her

Manhattan dwelling on 136th Street. Because A'Lelia adored the

company of lesbians and gay men, her parties had a distinctly

gay ambience. Elegant homosexuals such as Edward Perry, Edna

Thomas. Harold Jackman, and Caska Bonds were her closest

friends. So were scores of white celebrities. Novelist Marjorie

Worthington would later remember.

HARLEM HOSTESS. Parties

were the hub of Harlem's nocturnal culture, and they helped

grease the social Renaissance. The most official of these events

were held at the Civic Club and the most proper consisted of

Sunday afternoon literary talks, often in French, at Jessie

Fauset's home, or in one of the Dunbar Apartments. The most

lavish parties were undoubtedly those thrown by A'Lelia Walker,

the hostess of the Renaissance. Standing six feet tall, her

statuesque presence was emphasized by high heels and tall

plumes. The four- times-married heiress wore silk dresses and

ermine coatees, paisley beaded shawls from Wanamaker's, and

sable muffs, and her well-modeled head and cocoa complexion were

set off by silver turbans. "She looked like a queen," observed

Carl Van Vechten, "and frequently acted like a tyrant." A'Lelia

could afford to do both.

The hundreds of parties

she threw during the 1920s were financed by the fortune she

inherited from her mother, Madame C. J. Walker, whose life

provides the most inspirational of black Horatio Alger stories.

An orphaned child of ex-slave sharecroppers, she worked as a

washerwoman. As a result of stress and poor diet, her hair began

falling out when, about 1903, a large black man appeared to her

in a dream and revealed a secret recipe to combat baldness. She

decided to invest in her vision, and with capital of $1.50, she

started a hair- straightening empire that marketed "Madame

Walker's Wonderful Hair Grower" and adapted "hot combs" to

straighten the hair of black women. At the time of her death in

1919, her enterprise had yielded over $2 million as well as a

mansion called the Villa Lewaro. In contrast to her mother,

A'Lelia invested her energy neither in the hair culture business

nor in her mother's favorite charities (her will earmarked

two-thirds of the profits from the Walker empire for charity).

A'Lelia instead devoted herself to developing a Harlem high

society that included whites and blacks, royalty and racketeers,

lesbians and homosexual men, writers and singers. Her guest

list, one observer reported, "read like a blue book of the seven

arts," and her parties provided an Uptown counterpart to those

Carl Van Vechten threw Downtown.

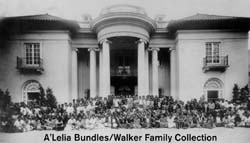

Walker Agents Convention Delegates at Villa Lewaro,

1924 -- Photograph courtesy of A'Lelia

Bundles/Walker Family Collection.

Walker Agents Convention Delegates at Villa Lewaro,

1924 -- Photograph courtesy of A'Lelia

Bundles/Walker Family Collection. |

A'Lelia's most elegant

parties were held at the Villa Lewaro, her cream- colored

Italianate mansion fifteen miles up the Hudson in Irvington,

designed by Vertner Woodson Tandy, the first African American

licensed to practice architecture in New York State. A'Lelia was

afraid to stay at the villa alone (it was here that her mother

had died of Bright's disease in 1919), so she invited guests for

long weekends of ostentatious luxury. They were met by black

servants in white wig, doublet, and hose and encouraged to rest

in Hepplewhite furniture while enjoying her $60,000 Estey pipe

organ or her twenty-four-carat gold-plated piano.

Although those weekends

were the most extravagant of A'Lelia's events, the most widely

attended took place in her Harlem mansion at 108-110 West 136th

Street--which she named “The Dark Tower" after Countee Cullen's

column by that name. In the fall of 1928, A'Lelia announced her

interest in Harlem's cultural life. She joined her twin

limestone townhouses, and, inspired by bohemian friends, she

envisioned music being played there, paintings and sculpture on

view, and poetry read. Although no one thought her new pursuit

could compete with her passions for shopping, poker, and bridge,

they were impressed that she transformed her new cultural

enthusiasm into an ongoing salon. She named her salon "the Dark

Tower" after Countee Cullen's column in Opportunity, and she had

Langston Hughes's "The Weary Blues" lettered on one wall. Guests

entered through long French doors and stepped onto the

blue-velvet runner that led into a splendid tearoom. They

checked their hats for 15 cents and listened to a talking

parrot. One might remain below to drink and dance on the parquet

floor, or ascend to the top-floor library for conversation and

bridge, surrounded by bookcases containing works written by

African Americans.

|

| Walker (left), c.

1930s |

| Underwood & Underwood/

Corbis-Bettmann |

|

Everything in A'Lelia's

parlor-cum-tearoom-salon represented the ostentatious best that

money could buy: the designer was Paul Frankel; the carpet,

Aubusson; the furniture, Louis XIV; the turquoise and amethyst

paste tea service, Sèvres; the drink, champagne. Sometimes the

music issued from a sky-blue Victrola, but more often someone

played a Knabe baby grand piano. Fresh from the Broadway revues

were Alberta Hunter, Adelaide Hall, and the Four Bon Bons.

Nightclub crooners included Jimmie Daniels and Gus Simons, and

Taylor Gordon sang spirituals. A'Lelia's ever-present

retinue-Wallace Thurman dubbed them ladies- in-waiting- included

striking light-skinned women (actress Edna Thomas, Mayme White,

Mae Fain) and witty homosexual men (Casca Bonds, Edward Perry)

who organized the socials. For one of her most notorious (and

possibly apocryphal) parties, she reversed the favors usually

accorded the races-white guests were served pig's feet,

chitterlings, and bathtub gin, while the black guests, seated in

separate and more posh quarters, dined on caviar, pheasant, and

champagne.

The Dark Tower was a

fashion showcase, with blacks and whites showing off to one

another. Bon vivant novelist Max Ewing described one evening to

his parents in Ohio: "You have never seen such clothes as

millionaire Negroes get into. They are more gorgeous than a

Ziegfeld finale. They do not stop at fur coats made of merely

one kind of fur. They add collars of ermine to gray fur, or

black fur collars to ermine. Ropes of jewels and trailing silks

of all bright colors."

Some of A'Lelia's guests

relished her extravaganzas while simultaneously looking upon

their hostess-dubbed the "dekink heiress" and the "Mahogany

Millionairess"-as a dubious flowering of Negritude. Some artists

avoided A'Lelia's, as Richard Bruce Nugent recalled, "Because

actually it was a place for A'Lelia to show off her blackness to

whites." A'Lelia's fortune sprang from Negroes' aspiration to

appear more European-even though Madame Walker insisted this had

never been her intention. A'Lelia's favorite cabaret,

white-owned Connie's Inn, discriminated against less-wealthy

blacks. Although she supported Harlem culture, she had little

interest in intellectual talk and rarely read books; one

acquaintance cattily declared seven minutes to be her limit for

elevated conversation. Whatever her limitations, she managed to

surround herself with titled Europeans; bosses of Wall Street;

members of the Social Register; leaders of music, stage, and

literature. As Richard Bruce Nugent observed, she "had made her

bid for space on the upper rungs of the sepia social ladder."

In some ways, The Dark

Tower served to reinforce the prejudice some in the black

community had against Walker; she was sometimes seen as more

interested in presenting authentic "Negro" culture for the

benefit of her white acquaintances that actually promoting it

with financial support. On one occasion, in what would become an

apocryphal tale of the Harlem Renaissance, Walker separated her

guests by color and served whites chitterlings and bathtub gin,

while blacks enjoyed champagne and caviar. Some among Harlem's

upper stratosphere even snubbed her for being the daughter of a

washerwoman--despite the fact her mother was the country's first

female self-made African American millionaire. Privately,

elitist lighter-skinned blacks dismissed Walker as "the Mahogany

Millionairess." Walker was also quite tolerant of gays among her

social set, which also set her at odds with some of Harlem's

more conservative hierarchy. Grace Nail Johnson, the wife of

novelist James Weldon Johnson and considered the grand dame of

Harlem society, remained adamant about never crossing the

threshold of Walker's residences nor The Dark Tower.

As the decade waned, Walker continued to entertain lavishly,

though years of excessive indulgence of both food and alcohol

were taking their toll on her six-foot frame. The parties came

to an end, however, with the onset of the Great Depression in

1929. The Madam C. J. Walker & Company, with its massive

Indianapolis plant and national distribution network, began to

feel the impact of the economic misfortune early on. The heiress

shuttered The Dark Tower in 1930, and the following year

auctioned off some of the antiques and luxuries housed at Villa

Lewaro; she also divorced Kennedy. On August 16, 1931, the New

York Times announced that Walker had expired in the early

morning hours of that same day. Walker had been hosting a

birthday party for a friend at a house in Long Branch, New

Jersey.

Much of Harlem turned out for Walker's memorable funeral. Noted

minister Adam Clayton Powell Sr. eulogized her; college founder

Mary McLeod Bethune spoke of the legacy left by both Walker and

her mother, and Langston Hughes contributed a poem, "To A'Lelia,"

which read, in part: "So all who love laughter/And joy and

light,/Let your prayers be as roses/For this queen of the

night." When she died in 1931, Hughes wrote that her

passing marked the end of the Harlem Renaissance.

Source:

http://xroads.virginia.edu/~UG97/blues/garber.html

http://xroads.virginia.edu/~UG97/blues/watson.html

http://www.aaregistry.com/african_american_history/923/ALelia_Walker_Harlem_businesswoman

http://www.madamcjwalker.com/alelia.html

http://www.africanpubs.com/Apps/bios/0016WalkerA.asp?pic=none

|