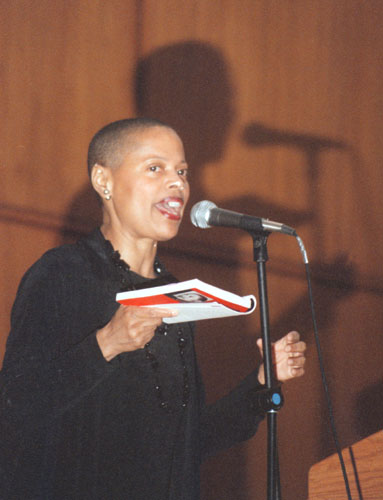

(Ramona Lofton)

Poet/Author

FemmeNoir

A Web Portal For Lesbians Of Color

Ramona Lofton, better known to her readers as Sapphire, was born in 1950 in Fort Orr, California. On the surface, her family was characterized as the normal, middle class family. Her father was an army sergeant and her mother was a member of the Women's Army Corps. As a child, Sapphire's family relocated several time to various cities, states, and countries. When she was only 13 years old, Sapphire's mother became the victim of alcoholism and eventually departed from her life. Her mother eventually died in 1983. In that same year, her brother, who was then homeless was killed in a public park.

Sapphire attended San Francisco City College in the 1970's majoring first in chemistry and then switching to dance. She soon dropped out to become a hippie and moved to New York in 1977 taking several odd jobs, including topless dancing and housekeeping. It wasn't until the early 1980s that she began writing poetry and reading it aloud at various Village venues including the Nuyorican Cafe. Sapphire eventually returned to school and graduated with honors in 1993 with a degree in modern dance. Upon graduation, she taught reading to students in the Bronx and Harlem and also enrolled in graduate school at Brooklyn College.

Single-monikered literary icon Sapphire has

been called many names. A writer whose art grapples with diverse

identities and marginalized communities, she often finds herself

under attack, not least because she challenges the very groups

with which she identifies. She reminisces, "In the ’80s I’d be

in front of a black audience reading about a black woman eating

a white woman's pussy, and I was considered a deviant traitor."

At an event in Chicago, where she was billed as a lesbian

author, she faced the wrath of two female audience members

furious at what they considered to be Sapphire's deliberately

faux-lesbian performance. Seems her reading wasn't Sapphic

enough. But she doesn't flinch away from people who try to

simplify her particular mélange of identity and sociopolitics

with attempts to label and limit her scope. Expressing the

difficult locus where revelation meets revolution is her

signature fusion, a fierce combination of confessional and

political metamorphoses.

Her

groundbreaking, autobiographical book of poetry American

Dreams (1994) probed the brutal legacy of childhood sexual

abuse, while her second book and debut novel, Push

(1996), ushered her into mainstream success and celebrity. The

critically acclaimed novel was a controversial examination of

the intersections of urban poverty, literacy, incest, and AIDS

in the life of protagonist Precious Jones, a teen mother

learning to read and finding autonomy despite desperate

circumstances. "I feel great about Push," she says.

"They're reading that book in Guadalupe. It's been translated

into French, which means in all of West Africa, there's the

possibility of it being a weapon against HIV and homophobia."

Her

groundbreaking, autobiographical book of poetry American

Dreams (1994) probed the brutal legacy of childhood sexual

abuse, while her second book and debut novel, Push

(1996), ushered her into mainstream success and celebrity. The

critically acclaimed novel was a controversial examination of

the intersections of urban poverty, literacy, incest, and AIDS

in the life of protagonist Precious Jones, a teen mother

learning to read and finding autonomy despite desperate

circumstances. "I feel great about Push," she says.

"They're reading that book in Guadalupe. It's been translated

into French, which means in all of West Africa, there's the

possibility of it being a weapon against HIV and homophobia."

Sapphire is following Push with a book of poetry,

Black Wings & Blind Angels (Knopf, 130 pp., $20), keeping

her poetic voice limber. "To me," she says, "poetry is like a

language, a language I want to keep up." Here, her

characteristic intensity mixes with classical as well as

experimental forms, excavating dreams, memory, and history to

address a multitude of topics, police brutality and sexual

identity among them. In quieter moments she gracefully examines

the fear of making love with the lights on, meditating on the

eroticism of a body not in its idealized youthful form. Even in

Black Wings's more harrowing poems, sestinas abound,

lending a sharp, disciplined edge to unwieldy memories of

childhood abandonment and rape.

This engagement with formal poetics marks a significant change

of perspective for Sapphire. Forgiving her sexually abusive late

father after decades of rage, she's offering themes beyond her

personal-healing manifestos. "Healing is a good state," she

says, "but it's also all-consuming. Somewhere past healing you

get what they promise you, you get your life back. You get to

explore other things. It's like that Buddhist aphorism, 'The

barn has burnt down and now I can see the moon.' "

Moving

past the work of survival, she says, and linking it to political

realities outside one's personal scope, is critical for social

change. In Black Wings, Sapphire takes aim at American

institutions that effectively sanction racist violence. A series

of poems, "Gorilla in the Mist," which was begun in

American Dreams and continues in the new volume, explores

paradoxical constructions of black male sexuality as much as it

does police brutality, graphically imagining the psyches of

racist cops. In another poem, "Looking at Plate No. 4: 'Homicide

Body of John Rodgers, 883 W. 134th Street, Christensen, October

21, 1915,' " she muses on a real-life episode described in

Luc Sante's Evidence, in which a murdered black man was

photographed with his penis exposed, a post-mortem indignity

that would not have been inflicted on a white victim.

Moving

past the work of survival, she says, and linking it to political

realities outside one's personal scope, is critical for social

change. In Black Wings, Sapphire takes aim at American

institutions that effectively sanction racist violence. A series

of poems, "Gorilla in the Mist," which was begun in

American Dreams and continues in the new volume, explores

paradoxical constructions of black male sexuality as much as it

does police brutality, graphically imagining the psyches of

racist cops. In another poem, "Looking at Plate No. 4: 'Homicide

Body of John Rodgers, 883 W. 134th Street, Christensen, October

21, 1915,' " she muses on a real-life episode described in

Luc Sante's Evidence, in which a murdered black man was

photographed with his penis exposed, a post-mortem indignity

that would not have been inflicted on a white victim.

For Sapphire, forgiving her father was a crucial step in being

able to address the complex range of social injustices facing

African American men. In a long prose poem, "My Father Meets

God (or, The Dream of Forgiveness)," she portrays her father

meeting God in the afterlife, recalling pivotal points of his

life in a fluttery stream-of-consciousness. Regarding Sapphire,

the father in the poem feels a mixture of pride for what she's

made of herself ("Look at your girl lift up the people; she's

the nurse, teacher (poet/healer) you always wanted her to be")

and regret for how he hurt her. Ultimately, the daughter's

strength redeems the father: "Look look see Sapphire shine. She

changed it for you, the past. That's what children are for."

Sapphire knows the past is not entirely changeable, but that it

can be transcended and transformed. Known for years as an out

lesbian feminist, Sapphire has, in her new book, revealed her

bisexuality. Following the poem "A Window Opens" is a rather

blunt and oddly stiff explanatory note about this change.

Shrugging off the label "lesbian" is certain to prove no easier

than shouldering it, but, as always, she is ready for the

discussion. "As much oppression as I took on when I came out as

a lesbian, the gay community was also a safe place for me. And

that was okay for a little while, but then that safety became a

box. I made a big statement when I came out, and since that

statement is no longer holding true, I need to make another

statement about where I'm really at." Sapphire's readers should

know by now that her work ruthlessly challenges accepted norms

and attitudes about women, sexuality, race, and politics. And

the poet knows her readers: "My audience includes people who can

or would like to understand the process of personal

transformation, people who understand putting yourself out

there. There are those who, whether or not they agree with where

I'm going, are serious about telling the truth about life and

therefore will be serious about me and my work."

Sapphire is hoping for a dialogue among women who are ruled by

desire, in part because the prevailing discussion of mutable

sexual identity seems too simplistic. "The world is not black or

white," she says, "the transgender movement is showing us that

it's not strictly male or female, there's a whole wilderness in

between." If separatist ideologies polarized and simplified

genders, Sapphire is excited by the possibilities for

multiplicity, pleasure, and inclusive sexual politics she sees

pulsing in younger feminists. She claims, "These women are gonna

have their sexualities, with men, with other women. I think

that's big progress."

Moving along herself, she wonders aloud whether these themes of

sexual identity will resurface in the novel she's working on.

"We'll see," she says. But one thing is for certain: "This is my

last public coming-out statement." Sapphire's last word can be

taken as the first word in the push-and-pull of a controversial

dialogue, possibly leading toward the kind of inclusiveness that

the poet herself insists on. As she says in "A Window Opens":

"It's about opening, being vulnerable, coming out front with my

desire, being clear after all these years."

PRECIOUS WORDS - Sapphire speaks about Push

Interview by Darius Casey

Text by

The opening lines of Sapphire's Push might not be music to some ears, but they ring true: "I was left back when I was twelve because I had a baby for my fahver. That was in 1983. I was out of school for a year. This gonna be my second baby. My daughter got Down Sinder. She's retarded."

With about 150 pages of jagged words like these, African-American poet, teacher and novelist Sapphire burst on the modern literary scene, landing a $500,000, 2-book deal with Knopf. Push centers on the writings of Precious, a 16-year-old girl who, after enduring molestation and violence by her parents, seeks a better life for herself through education. The critics are split; some say Push is a brilliant account of ghetto life, some say Precious is simply a "stand-in for polemic" (Ellen Levy , City Pages). This is what Sapphire says:

Home