Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar-Nelson

(1875-1935)

Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar-Nelson

(1875-1935)Author/Activist/Educator

FemmeNoir

A Web Portal For Lesbians Of Color

Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar-Nelson

(1875-1935)

Alice Ruth Moore Dunbar-Nelson

(1875-1935)Alice Dunbar-Nelson was born on July 19, 1875, as Alice Ruth Moore, in New Orleans, Louisiana of African American, Native American and Caucasian ancestry. She attended public school in New Orleans and enrolled in a teacher's training program at Straight University (now Dillard University) in 1890. Upon receiving her degree in 1892, she began teaching in New Orleans.

Three years later in 1895, Alice Ruth Moore published her first book, Violets and Other Tales, which was a mixture of short stories, poetry, sketches, etc., which would begin a multifaceted career as an author of many genres, including fiction, drama, and newspaper journalism. In 1897, Moore moved to Brooklyn, New York, where she taught at the White Rose Mission. At this time Moore began corresponding with the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar and in March, 8, 1898, she married Dunbar and moved to Washington, D.C. The marriage lasted until 1902, when they were legally separated; Dunbar died on February 6, 1906.

Following her separation from Paul Laurence Dunbar, Alice Dunbar moved to Wilmington, Delaware. She took a position as a teacher and administrator at Howard High School which she held until 1920. During this period she also directed the summer session for in-service teachers at State College for Colored Students (the predecessor of Delaware State College) in Dover, and taught two years in the summer session at the Hampton Institute. In 1907, she took a leave of absence from her teaching position in Wilmington and enrolled as a student at Cornell University, returning to Wilmington in 1908. In April, 1916, Alice Dunbar married Robert J. Nelson, a journalist, politician, and civil rights activist.

Although

Alice Dunbar-Nelson had been active in social, political, and

cultural organizations since her youth, this involvement

increased around the time of her marriage to Robert Nelson. She

was extremely active in Delaware and regional politics, as well

as in the emerging civil rights and women's suffrage movements.

In 1915, she was field organizer for the Middle Atlantic States

in the campaign for women's suffrage. During World War I,

Dunbar-Nelson served as a field representative of the Woman's

Committee of the Council of National Defense. Subsequently she

served on the State Republican Committee of Delaware and helped

direct political activities among black women. From 1928-1931,

she was executive secretary of the American Friends Inter-Racial

Peace Committee.

Although

Alice Dunbar-Nelson had been active in social, political, and

cultural organizations since her youth, this involvement

increased around the time of her marriage to Robert Nelson. She

was extremely active in Delaware and regional politics, as well

as in the emerging civil rights and women's suffrage movements.

In 1915, she was field organizer for the Middle Atlantic States

in the campaign for women's suffrage. During World War I,

Dunbar-Nelson served as a field representative of the Woman's

Committee of the Council of National Defense. Subsequently she

served on the State Republican Committee of Delaware and helped

direct political activities among black women. From 1928-1931,

she was executive secretary of the American Friends Inter-Racial

Peace Committee.

From 1920-1922, Alice Dunbar-Nelson, together with Robert Nelson, was co-editor and publisher of the Wilmington Advocate, a progressive Black newspaper. From this period on, Dunbar-Nelson maintained an active career as a journalist. She was a highly successful syndicated columnist and wrote numerous reviews and essays for newspapers, magazines, and academic journals. Dunbar-Nelson also continued to write stories, poems, plays, and novels, much of which remains unpublished.

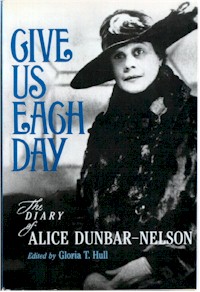

During the 1920s and 1930s, Alice Dunbar-Nelson's prominence as a political and social activist reached its high point. She reached a wide audience through her journalism; she was also in demand as a public speaker and gave numerous lectures and speeches on political, social, and cultural topics. Alice Dunbar-Nelson's life and career during this period is documented in detail in her diaries. Although Alice Dunbar-Nelson appears to have maintained a daily diary for most of her adult life, surviving portions bulk for the period 1921-1931. These surviving examples offer a comprehensive look at Dunbar-Nelson's daily activities for the most productive period of her career.

In 1932, Alice Dunbar-Nelson moved from Delaware to Philadelphia when Robert Nelson took a position as a member of the Pennsylvania Athletic Commission. By this time Alice Dunbar-Nelson's health had begun to deteriorate and she was frequently ill. In September, 1935, she was admitted to the hospital with a heart ailment from which she did not recover. Alice Dunbar-Nelson died on September 18, 1935, at the age of sixty.

Alice Ruth Moore’s work included themes of New Orleans and Creole life, and also frankly confronted the race problem and the issues of "passing" and the "color line". A portion of her Cornell University master's thesis on Milton and Wordsworth was published in the highly respected journal Modern Language Notes in 1909. She was widely published in journals, gave many speeches, and wrote newspaper columns for the Pittsburgh Courier and the Washington Eagle. Her greatest contribution to the field of Black women's literature is the diary she kept in the 1920s and 30s. Being one of only two full-length diaries written by nineteenth century Black women, it addresses areas of sexuality, family, health, work, and writing; it documents the existence of an active Black lesbian network and her relationships with several prominent women. (The other diary in existence is written by Charlotte Forten).

Her activist work in race relations and suffrage included serving on the Delaware state republican committee and directing campaign activities among African American women, heading the Delaware Crusaders for the Dyer Anti- Lynching Bill, and being a member of the delegation that addressed President Warren Harding at the White House on the issue of African American concerns. A prominent clubwoman and feminist, she was the field organizer for women's suffrage for the Middle Atlantic states. She was a co-founder of the Industrial School for Colored Girls, in Marshallton, DE, where from 1924-28 she served as parole officer and teacher. She served as the executive secretary for the American Inter-Racial Peace Committee from 1928-1931, in which capacity she traveled widely, giving speeches and organizing programs.

Dunbar-Nelson, who was very light

complexioned, often passed for white, and was sometimes

frustrated in her relations with darker-skinned African

Americans because of it. A complex woman who was a poet,

journalist, playwright, and unpublished novelist, Alice engaged

in intimate relationships with both men and women. One sonnet

was almost certainly written for one of her female lovers, Fay

Jackson Robinson, a newspaperwoman and socialite whom Alice met

during a trip to California.

Source: Women of Color Women of

Word --

http://www.scils.rutgers.edu/~cybers/dunbar-nelson.html

http://www.english.uiuc.edu/maps/poets/a_f/dunbar-nelson/dunbar-nelson.htm

|

Articles and Books by Alice Dunbar-Nelson:

|

|

Works of Alice Dunbar Nelson (Schomburg Library on

Nineteenth-Century Black Women Writers) |

Home