Sharon Bridgforth

Author, Poet, Performance Artist, and Playwright

Sharon Bridgforth grew up in segregated Los

Angeles surrounded by sweet and strong story-telling Southern

black single women who urged her toward a life of stability as a

schoolteacher. They had left their Southern homes and families

to flee the oppression of racism, to search for hope for their

children, and to be free of "family speculation" for themselves,

Bridgforth says. "Everybody was in everybody's business."

But she didn't develop a yearning for the stability her family

wanted for her. Through card parties and beach parties filled

with laughter, music on the radio, and lots of dancing and tale

telling, she did develop a love for her family's words, their

voices, and their stories. "Everything about me was informed by

who they were," she says. It was a love that was further fed

with summertime trips to Memphis and more stories, voices,

Southern words, and Mississippi blues. Its music wraps itself

around her writing like Southern humidity. In fact, you can

smell the Mississippi in Bridgforth's writing -- its flowing

waters of unconditional love she felt from her Memphis relatives

and the storms they experienced as black Americans.

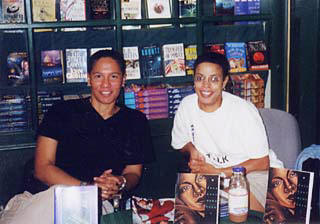

Bridgforth and

RedBone Press publisher Lisa Moore at Brentano's Bookstore in

Cleveland in June

photo by Lincoln

Pettaway

She hears it and feels it when she writes. She listens to its

music "as a tool to get me to that place where I can feel," as

she points to her heart, "in here." "the bull-jean stories is

structured the way it is on the page," she explains, "because I

was trying to capture the way that I heard my older family

members tell stories." It is written in all lowercase.

"Lowercase," she says, "feels more like the language sounds to

me."

As Bridgforth returned to the palm trees of L.A. and rode

crosstown bus after crosstown bus, from South Central L.A. to

her Catholic school in Echo Park, she read and daydreamed. She

was becoming a storyteller and author in her own right, despite

not knowing any writers, despite not discovering black writers

like Langston Hughes and James Baldwin until high school,

despite not even imagining becoming a writer.

But just like her wy'mn relatives had felt trapped in the South,

Bridgforth felt trapped in L.A. "I was suffocating. I was dying.

L.A. was killing me." She cannot seem to find enough verbs to

express her L.A. suffocation. "I felt so hopeless because it was

so big and mean and expensive. ... I think I needed to get away

from it in order to imagine myself." She just wanted to dream.

Friends in Texas beckoned her to Austin. Despite a fear of the

Klan and worry over intolerance toward gays and lesbians, she

heeded the call and took a job with the Health Department. It

was, as they say in Hollywood high-concept screenwriting, an

"epiphany." Through her work at the Health Department,

Bridgforth was "out and about in the community" and heard story

after story about "older black women who had lived with Miss

So-and-so for a long time." She started thinking about that.

Lesbians, she clearly realized. And Bridgforth was in awe that

there were black lesbians who were an integral, active,

well-respected, and well-accepted part of the community.

About the same time, Bridgforth was grieving for some of her

elderly family members who had died and was yearning to hear

their voices again. She sat down and wrote a story, combining

the women she missed with the women she was curious about in

Austin. And bull-jean was born. She was structured the way

Bridgforth had heard her family members tell stories -- a little

singing, a little dancing, a little poetry. It was 1993, and as

soon as Bridgforth finished that story, another story about

bull-jean flowed from her hands and mind, and then another, and

another. Bridgforth couldn't stop her. Bull-jean was now a part

of Bridgforth, just like her family was.

And so was writing. "It's like breathing," she says. "It's how I

understand myself and my life, how I look at the world, how I

appreciate those who came before me." It is her life, not her

work.

Susan Post, proprietor of Book Woman and, perhaps, Bridgforth's

biggest fan, can't remember how or when they met. "It seems like

I've known her forever," she says. Post believes there's a

psychic connection between Bridgforth and herself; every piece

of Bridgforth's writing tingles her spine and gives her

goosebumps. "Haunting," she calls the work. Bridgforth says that

Post would be "upset" for her when she received rejections. And

Bridgforth did receive rejection after rejection for bull-jean.

Like every writer who gets even one rejection, she got the down

in the dirty, dejected, rejected blues. We're talking Bessie

Smith blues because no one, not no one, wanted to publish

bull-jean. The theatre pieces sounded too much like poems. The

poems sounded too much like short stories. The stories ... well,

they were filled with "too much cussing. The subject matter's

too risky." There aren't a lot of white small presses willing to

publish fiction about a Southern black lesbian. And there

certainly aren't a lot of large New York City,

conglomerate-owned presses willing to publish fiction about a

Southern black lesbian. It's just not a niche that's profitable.

And while white presses thought bull-jean was too black, black

presses thought bull-jean was too gay. But the rejections may

also have had to do with publishers' befuddlement about how to

sell a work that defies easy categorization. Is the bull-jean

stories fiction, as Bridgforth calls it? Perfomance pieces?

Poetry? "The way that I write is all of those things,"

Bridgforth explains. Her voice soars an octave as she laughs and

admits that she just might have to die if someone insisted she

write in only one style. "I wouldn't be able to separate that

out. It's not my style." She adds, "I think we're complicated,

complex beings, and that's a good thing. So for me, it's in

recognition and honor and celebration of my own complexity to

not separate out my pieces, my bits, my parts." She insists that

she doesn't even use dialogue in her fiction. "It's more

monologues, poems, songs, responding -- where people are

responding to each other or responding to what's going on ... as

opposed to direct conversations."

So time after time, Susan Post stared Bridgforth right in the

eyes and said, "Your time is going to come, and there is no

doubt about it." She swore to Bridgforth that if bull-jean

didn't get published, she was going to take Bridgforth to Book

Expo America, the publishing industry's major annual gathering,

and lead her, by the hand, to every publisher she knew. Post was

bound and determined to get bull-jean to the public. "It wasn't

like the scrub girl who hadn't yet become Cinderella," Post

explains. "She was already Cinderella. She was wearing the right

shoes."

Indeed, realizing that if she didn't do it herself that she

wouldn't have "a place to talk from," and also wanting to make

sure that her works were performed the way she wanted -- "no

words added, shifted around, or changed" -- Bridgforth

established her own theatre company called root wy'mn. That was

1993, the same year she birthed bull-jean, and over time root

wy'mn toured her plays lovve/rituals & rage, no mo blues, and

dyke/warrior-prayers from Boston to Berkeley.

Bridgforth promoted her work and herself. That included

attending a 1997 Lambda writers conference in Washington, D.C.,

where she talked with Lisa Moore, a young black lesbian from

Atlanta who had started her own small press, RedBone Press. It

was a one-woman operation solely dedicated to publishing black

lesbian writers. It would become a match made in heaven.

Already, Lisa Moore was aware of Bridgforth. At the

encouragement of writer Shay Youngblood, Bridgforth had

submitted a story to RedBone's first publication, does your mama

know?, an anthology of black lesbian coming-out stories. Moore

accepted Bridgforth's piece, "that beat," in 1995. That same

year, at the Michigan Womyn's Music Festival, Moore saw no mo

blues, which has a lot of bull-jean in it. Then, Moore came to

Austin and saw Bridgforth's blood pudding, and also applied to

graduate school at the University of Texas. That was 1998, the

year that Bridgforth, Moore, and Post will never forget.

It was the start of a continuing business affair between

Bridgforth and RedBone and Bridgforth and the Lambda Awards

because at the Lambda writers' conference, Bridgforth told Moore

she was going to submit more bull-jean to the publisher. She

did, and in the spring of 1998, after Moore wrestled with the

fact that bull-jean sounded like poetry (she didn't publish

poetry), RedBone and Bridgforth contracted for the bull-jean

stories. In June of that same year, RedBone won two Lambda

Awards -- "Lesbian Studies" and "Best Small Press Book" for does

your mama know? Bridgforth was suddenly a part of a

Lambda-winning project. And Moore moved to Austin to begin

graduate studies and publish the bull-jean stories.

Bridgforth realized that she didn't have time to do both root

wy'mn and write. So she prioritized. Writing won. Root wy'mn

closed. And the bull-jean stories was published. Moore backed

the book with as much promotional budget and time and energy as

she could afford, which wasn't much since she publishes on a

shoestring budget. But she is a woman who is loyal and

determined and who is in love with bull-jean.

"Her voice," says Moore, "the way she spoke, it seems like

home." Moore's father is New Orleans blues man Deacon John. She

also liked the fact that bull-jean was situated in a community

and "belonged somewhere." So Moore faxed and phoned and flew

Bridgforth around the country until bull-jean was in the hands

of independent stores throughout the nation ... and Canada.

The following year, bull-jean won RedBone and Bridgforth another

Lambda Award for, again, lesbian and gay small press book. The

first person Bridgforth thanked at the awards ceremony was Book

Woman's Susan Post. "Her inner place seems to be deeply

anchored," Post says about Bridgforth. "So I don't think she can

be tossed too far." In other words, Bridgforth won't forget

those who helped her along the way.

Post is right; success has not jaded Sharon Bridgforth. But how

could it? She wants so much more -- a screenplay for bull-jean,

the gift of time to write, national theatres that can give

bull-jean the production values she deserves, to encourage and

mentor others as she has been encouraged and mentored. "I've

experienced bits of this," she acknowledges, "but I would like

to go full-steam."

This year, it looks as if RedBone Press will publish a book

that, for the first time in its history, does not involve Sharon

Bridgforth, who has been tucked away in Kyle writing, with

forays into the San Marcos Target and occasional trips to

Austin's Cafe Mundi to satisfy her city girl needs for noise.

Bridgforth received a 1999/2000 NEA/TCG Playwright's Residency

at Frontera @ Hyde Park and is working on a new theatre piece,

con flama, which was finished this summer and will be produced

by Frontera in September. It is about her time growing up in

L.A., "a look at the cultural landscapes of a place," "a ride

through a melting pot" of ethnicities and struggles.

| The CD the

bulljean stories is only available through RedBone Press or

at specific events. To order call RedBone Press at (202)

667-0392 or fax at (202) 667-0393. Send checks or money

orders to P.O. Box 15571, Washington, DC 20003. CDs cost

$12.99 and shipping is $3.20 (priority mail). You can also

order the book directly from Redbone Press at

redbonepress@yahoo.com. |

Source: Excerpt from

Other Voices, Other Rooms -- BY SUZY SPENCER

Website:

http://www.sharonbridgforth.com/

|